Key points

- We often think of negotiations as competitive interactions.

- Yet there are many times when negotiators who accommodate and build better relationships obtain better outcomes.

- In many cases, especially for services, the economic value of a negotiation depends on the post-negotiation relationship.

- In these contexts, soft—collaborative, accommodating—negotiators attain better economic outcomes than competitive negotiators.

Popular negotiation advice, reflected in books such as Start with No, Ask for More, or Never Split the Difference, tends to focus on aggressive strategies that will improve negotiated deal terms. But this advice may not necessarily improve your outcomes. By employing aggressive tactics, you might obtain great deal terms—but you may also ultimately harm your relationship with your counterpart in ways that negatively impact what happens after you complete your negotiation.

Our research focuses on when building a good relationship can improve your own economic outcome from the negotiation. In our recent work, we argue that many situations involve a post-negotiation interaction or post-negotiation work. In these cases, negotiators should care relatively more about building relationships—even at the cost of favorable deal terms.

Importantly, good relational outcomes can often boost economic value through post-negotiation behavior. And conversely, bad relational outcomes may harm overall economic value. For example, negotiating aggressively with a new hire might cause them to agree to a lower salary, but it might also harm their morale, their commitment to the organization, and their work effort. As a result, your ultimate outcome—even if you saved a few thousand dollars on salary—may be worse.

Popular negotiation advice and prior negotiation research has broadly conflated deal terms with economic outcomes. This work has implicitly assumed that a negotiated contract reflects a complete picture of the outcome. Though this may be true for some negotiations, such as buying a car, it is completely untrue for other negotiations, such as hiring a new employee.

When Should You Be Aggressive vs. Collaborative?

How do we know when to focus on deal terms versus relational outcomes? In our research, we introduce a novel way to characterize negotiation situations. Our approach underscores the importance of post-negotiation behavior, to identify when you should negotiate aggressively—and when you should not.

We introduce the term “Economic Relevance of negotiators’ Relational Outcomes” (abbreviated as ERRO) to describe when a great (vs. poor) relationship with your negotiation counterpart really matters after the negotiation. In many negotiations—particularly those involving services and employment—the total economic value negotiators derive from a negotiation includes both deal terms (e.g., how much an employer pays in wages) and post-negotiation behavior (e.g., how hard the employee works after receiving that wage—which depends on the relationship). ERRO reflects the extent to which a negotiator’s relational outcomes impact their counterpart’s post-negotiation behavior in a way that ultimately impact their final economic outcome.

For example, when you buy a BBQ grill, the price you pay may determine your economic outcome more than your relationship with the seller. However, when you hire a service provider (such as a babysitter, a caterer, or a contractor), a poor relationship following the negotiation may harm the economic value you derive from the agreement, and a positive relationship might increase the economic value you derive. Thus, negotiating to buy a BBQ grill is a low ERRO context, but negotiating with a babysitter is a high ERRO context.

Many experts have assumed a compensatory relationship between favorable economic outcomes and favorable relational outcomes: Better outcomes along one dimension come at the expense of the other dimension. Our research shows that in high ERRO contexts, better economic outcomes require better relationships. That is, in high ERRO contexts, the best way to obtain high economic value is to build a great relationship with your counterpart.

Applying ERRO to Your Own Negotiations

How should you approach a negotiation? First, figure out if you are in a high ERRO context or a low ERRO context. To do this, ask yourself the following questions:

After the negotiation is over, how important is it to you that your counterpart has high morale? Specifically, imagine that instead of developing a decent relationship with your counterpart, you had developed a great relationship with your counterpart. Would that great relationship improve the value of the outcome you receive? If instead, you had developed a poor relationship with your counterpart, would that poor relationship diminish the value you receive?

If the answer to these questions is “definitely yes,” a good relationship could really benefit you and a bad relationship could harm you, then you are in a high ERRO negotiation context. If the answer to these questions is “no,” then the deal terms matter a great deal more than relational outcomes and you are in a low ERRO negotiation context.

It is important to note that ERRO is determined not only by the negotiation setting but also by your specific “role” in the negotiation. For example, a negotiation could be high ERRO for one party (e.g., for the parent hiring the babysitter), but lower ERRO for the other (e.g., for the babysitter who has many other regular babysitting jobs). In sum, when considering how to negotiate—and how the other person might negotiate—you need to think about your own ERRO and your counterpart’s ERRO.

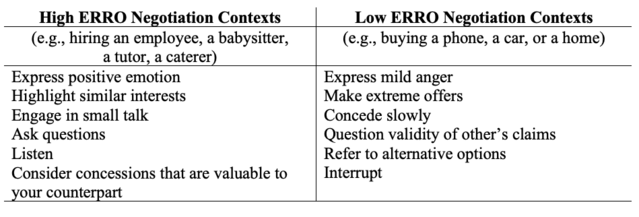

Understanding ERRO will help you tailor your negotiation strategies for the specific situation. In a low ERRO context (like buying that BBQ grill), aggressive or competitive tactics that sacrifice relational outcomes may work just fine. For example, in these contexts, you can make extreme offers, concede slowly, and try to “get more.” But in high ERRO contexts (think babysitter), collaborative tactics may get you the best outcome. In these cases, building a relationship and even accommodating your negotiation counterpart may yield the best outcomes.

By accounting for ERRO, our findings reveal when different tactics are likely to improve economic outcomes—and when they are likely to harm economic outcomes. We provide some examples in the table below.

What Our Research Found

In our research, we surveyed hundreds of users in two large online marketplaces, and we conducted laboratory experiments in which people negotiated with one another. We used a novel approach to studying negotiation. In contrast to the dominant paradigms that scholars have used to study negotiations, we did not end our studies when negotiators reached a deal (or reached an impasse). Instead, we included a post-negotiation stage. This is akin to negotiating a salary with a new employee—and then including a period in which they actually perform the work.

In our experiments, a Boss and a Worker first negotiate a salary. Then, after they reach an agreement, the Worker decides how much effort to exert on behalf of the Boss. The more effort the Worker invests, the higher the profit the Boss receives. In our studies, we manipulated ERRO, the relative importance of the Worker’s effort in determining the Boss’ economic outcome.

Our studies revealed several important results. First, by changing the economic importance of post-negotiation behavior, negotiators adopted different negotiation styles. In high ERRO contexts, compared to low ERRO contexts, negotiators: (1) were more concerned about their relationship with their counterpart, and (2) negotiated less competitively and more collaboratively (see examples in the table). That is, in low ERRO contexts, in which the relationship has low impact on post-negotiation economic outcomes, people negotiated more aggressively; in high ERRO contexts, people negotiated in a “softer” way and focused on building a good relationship with their counterpart.

Second, we found that the economic value of competitive and collaborative tactics was very different across the high- and low-ERRO contexts. That is, rather than a “one-negotiation-style-fits-all” approach, we found that collaborative negotiators obtained better economic outcomes in high ERRO contexts and that competitive negotiators obtained better economic outcomes in low ERRO contexts. Specifically, negotiators in high ERRO contexts (3) built better relationships that ultimately (4) motivated their negotiation counterparts to work harder after the negotiation. This boosted economic outcomes for collaborative negotiators in high ERRO contexts.

Compared to negotiators who built poor relationships, negotiators who built positive relationships with their counterparts attained better economic outcomes in high ERRO contexts, even when they obtained worse deal terms, because their counterparts invested greater effort following the negotiation.

When you enter a negotiation—whether you are hiring a new employee, purchasing property, or buying another company, keep the ERRO context in mind. In high ERRO negotiations, your economic outcome may be worse if you negotiate aggressively, even if you secure better deal terms.